Avant Garde is a seminal, but somewhat overlooked by a wider public, magazine, which broke taboos, rattled some nerves and made a few enemies. The magazine was the brainchild of Ralph Ginzburg, an eager and zealous publisher, even if the path that led to Avant Garde wasn’t so straightforward. It represents the third major collaboration between Ralph Ginzburg and Herb Lubalin, the magazine’s talented art director. The two previous magazines came to unexpected demise due to their candor and provocativeness, that landed them into legal trouble. Avant Garde is the magazine that gave birth to a much maligned and equally lauded typeface of the same name.

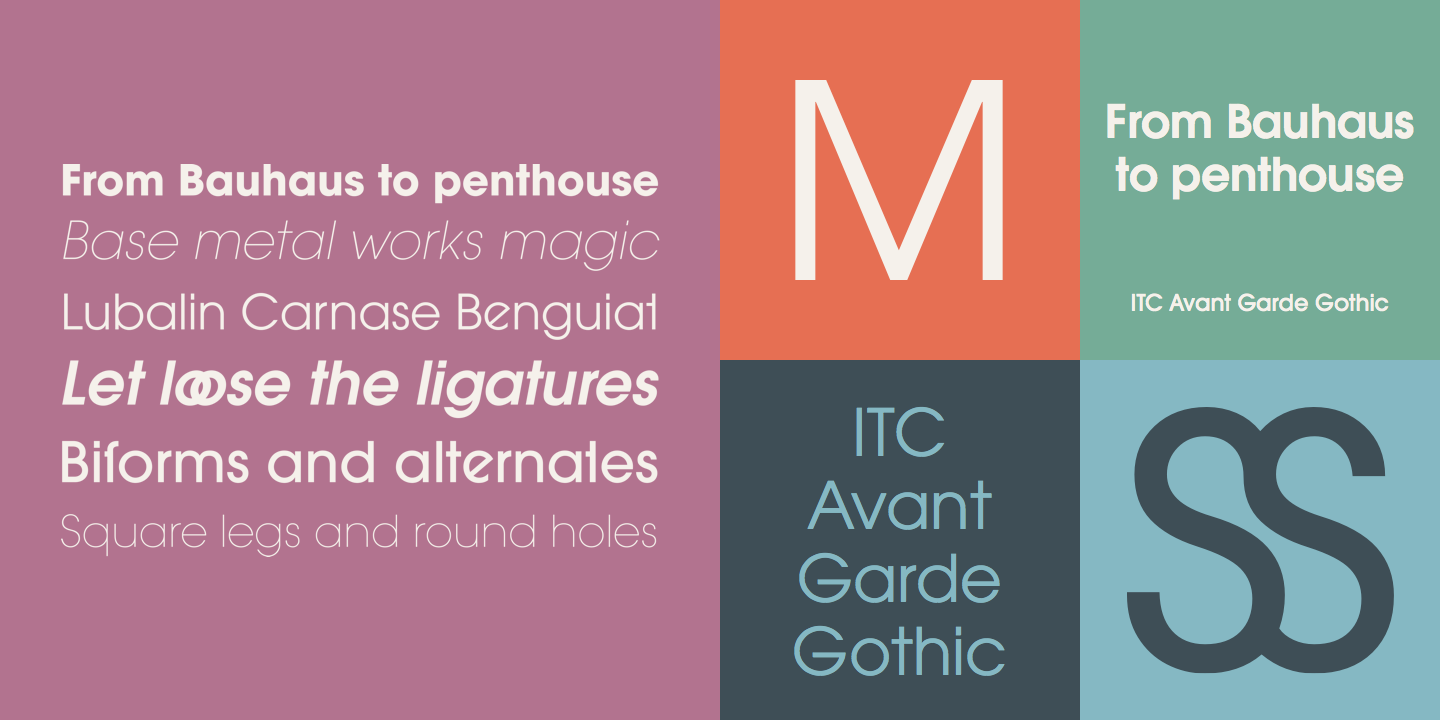

A typeface that reveled in the mutability of letterforms, exhibited brilliantly by its extensive set of ligatured characters. The magazine’s logo, which inspired the typeface, is a perfect encapsulation of what the magazine represented in 1968, the year the magazine launched: exciting, vibrant, edgy, with just the right amount of playfulness to move it out of the corporateness its geometric sans serif forms might otherwise imply. The magazine ran for 3 years, spanning 14 square-sized issues, and only folded due to Ralph Ginzburg losing his long-running legal battle with the US government over obscenity charges (partly stemming from Ralph’s and Herb’s first collaboration Eros magazine). The strong content and the inventive design of Avant Garde is a testament to a close understanding that developed between Ginzburg and Lubalin, but also of a mutual respect of the boundaries set by each side. Ralph didn’t interfere in the design and Herb didn’t meddle in the editorial content. It’s a balance that magazines still strive for today.

Avant Garde deserves a close investigation and appreciation. It still has a lot to say. — Alexander Tochilovsky. Crimes against typography are committed everyday.

But few typefaces have been victimized more than the late-sixties/early-seventies gothic Avant Garde – and the felonies persist. The reason is a surfeit of angular ligatures that offer too many cheap tricks. I know because I am a recovering Avant Garde abuser. Although I haven’t touched the stuff in almost thirty years, when the face was in its prime, I was hopelessly addicted.

Since I had the fonts on my Phototypositor I got kicks making the most flagrantly absurd ligature combinations imaginable. Nobody, not even the face’s creator Herb Lubalin, could stop me. In fact, having seen so many abominable applications by addicts like myself, I once heard Lubalin curse the day that Avant Garde was released to the public.

The Database Sql Generation Parameters File Could Not Be Loaded. However, the revenue stream made from font sales gives this a disingenuous ring. Avant Garde was not originally designed as a commercial typeface. It was the logo for a magazine that its editor and publisher Ralph Ginzburg explains was “a thoughtful, joyous magazine on art and politics” aimed at people “ahead of their time.” The goal of the magazine, however, was not merely to reflect the cultural zeitgeist but take a lead role in purveying raucous sixties culture. In other words, it was avant garde – thus the magazine’s title, coined by Ginzburg’s wife and collaborator, Shoshana, was Avant Garde.

The opening page of the first issue of Avant Garde bore this dedication set in Avant Garde Gothic: As most of the world's ills are traceable to old imperatives,old superstitions, and old fools, this magazine exuberantly dedicated to the future. Before launching the magazine Ginzburg was the publisher and editor — with Herb Lubalin the art director and designer—of the erotic hardcover magazine, EROS, which folded after four issues when Ginzburg was arrested and convicted on the charge of sending prurient materials (e.g. “pandering”) through the United States mails. After the trial Ginzburg wanted to start a new magazine but was prevented by his lawyers who feared it might turn out to be a “hellraiser.” Ginzburg was out on bail for the EROS conviction awaiting appeal, but the process took so long—about ten years—that the magazine ultimately went into production in mid-1967.

To help Lubalin develop the design scheme Ginzburg sent him a lengthy editorial outline and recalls, “He came up with two beautiful logos, but they were all wrong for the publication I had in mind.” One was based on the typeface used on the old original Coca-Cola bottles, another on Hebrew letters. “[Lubalin] kept associating the magazine with the nihilistic avant-garde school of art of the early 20th Century,” Ginzburg adds, “but this magazine had nothing to do with that.” Instead it was for intellectuals who might also possess a sense of humor. “Herb and I had always been on the same creative frequency.